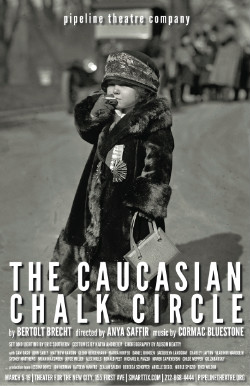

The Caucasian Chalk Circle

BOTTOM LINE: Good Brecht. See this if you think theater should have a conscience. Or if you loved those choose-your-own ending books as a kid.

Caucasian Chalk Circle is a very ambitious play. Brecht famously (or infamously, depending on who taught your favorite drama class) demands much of theater. Not just of actors, of direction, of design, of audience, but of Theater with a capital “T.” We are supposed to go into a performance with a set of ideas and go out of it having examined, perhaps even questioned or changed, those very same preconceptions. Pipeline Theater Company, founded in 2008, picks up the playwright’s gauntlet in their latest production. Do they rise to the challenge? Brecht would roll over in his grave if I made your decision for you.

The show is set in the late nineteenth-century and follows the story of an abandoned child and the search for his true maternity. Does he belong to the aristocratic mother who birthed him, or the peasant woman who risked all to raise him?

The set is lovely — war-torn Eastern Europe lovely — with splintered wood, rope bridges, undressed scaffolding and a rough, shredded curtain. The costumes are more or less true to the historical setting and do their job indicating station. The original music, interpreted live onstage, makes itself essential to the performance. Indeed, with song titles mounted above the set (though the choice of digital projection confuses me, given the overall aesthetic), allegorical lyrics, and tonal melodies throughout, the production is very much a musical.

The actors are clearly trained and deliver solid performances across the board. They understand Brechtian acting. Maura Hooper is the show’s sympathetic lead, Grusha. Gil Zabarsky is its Byronic hero, the judge Azdak. Jaquelyn Landgraf, as the Governor’s wife, is especially salient in her ability to toe the line between naturalism and hyperbole to embody just exactly the traits that the script requires of her character. However, the company too often seem to be coalescing more as a showcase than an ensemble, each vying for position as best character-actor rather than servant to the collective story. Each seems acutely aware of his or her moments to shine. For example, the comic male duo of John Early and Brian Maxsween, playing the doctors/architects/nurses/lawyers, are hysterical. But they are also hams, scene-stealers.

The best moments in the show, true to its theme, are those in which the entire company moves as one. In the opening scene, after lights out on a silent house, we hear banging and voices from an exit door. The “outside” world forces itself into the theater and the actors move slowly onto the set. Together, they take it in, stop to think, and then in shared organic motion, without speech or physical differentiation, begin cleaning it.

Saffir’s direction deserves praise. There are only a few decisions that do not seem to spring immediately from the script; the production could teach a college theory class. From the clothing racks onstage to the direct questioning of the audience to the tongue-in-cheek treatment of station (in a memorable moment, Azdak instructs the fleeing Grand Duke how to eat cheese like a poor man), we never forget the reality of the theatricality or the theatricality of reality. Through the countless court scenes (an especially brilliant “audition trial” by Zabarsky), and the not-court-scenes-staged-as-court-scenes (a beautiful moment in which the narrator offers us the thoughts that two characters can’t speak) we understand the complexities of every choice presented and the entire weight behind them.

Despite minor flaws (a two-year old child weighs more than that, puppet-masters), we leave the play, ultimately, as I believe Brecht intended: with a sense of the importance of correct decision-making. As Azdak says towards the end, “if you don’t treat it with respect, the law just disappears on you.”

(The Caucasian Chalk Circle plays at The Joyce and Seward Johnson Theater at Theater for the New City, 155 1st Ave, through March 19th. Performances are March 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, & 18 at 8pm, March 6, 13 at 3pm, and March 9 at 2pm & 8pm. Tickets are $18 ($15 for students). To reserve, visit smarttix.com or call 212-868-4444. For more information, visit pipelinetheater.org.)