The Boys Are Angry

By Jillie Mae Eddy; Directed by Sam Plattus

Part of the 2015 New York International Fringe Festival

Off Off Broadway, Play

Runs through 8.28.15

VENUE #17: The SoHo Playhouse, 15 Vandam Street

by Dan Dinero on 8.24.15

BOTTOM LINE: The Boys Are Angry asks what's worse, misogynistic hate or obsessive love?

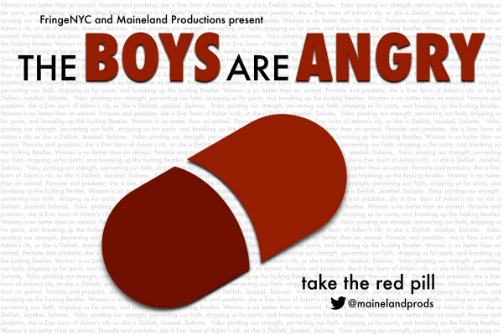

AJ is angry. Clearly he has every reason to be: he’s a straight white dude in his 20s, he lives in an enormous house his parents gave to him, and, with the rent he collects from his childhood friend Quinn, he has no need for outside employment, and spends most of his day not wearing pants. But privilege be damned—AJ, a Reddit philosopher and Men’s Rights blogger-activist, is mostly angry because he’s “taken the red pill” and knows the “truth” about women—that “Woman is the natural born enemy of man,” and that even though men are “losing the fucking battle,” women still want more. In many ways, Quinn is AJ’s opposite. He’s a “beta” to AJ’s “alpha,” soft-spoken as opposed to ranting, and dislikes most of what AJ says about women. Quinn is also handsome, polite, and gainfully employed, presumably any girl’s dream. And then there’s the girl who Quinn falls in love with. Apparently, at least to hear Quinn tell it, she’s perfect.

As played by Xander Johnson, AJ is immediately repellant, but also strangely alluring. The Boys Are Angry begins with Johnson delivering a lengthy diatribe, presumably one of AJ’s recent blog posts, that is at turns funny, shocking, and disturbing; it’s the kind of speech for which “trigger warnings” were invented. When Quinn (Nate Houran) comes home from work one day having met a girl (played by Eddy), AJ teases him about not moving fast enough. But Quinn wants to take things slow, so as not to ruin the new relationship. As time goes on, Quinn continues to see The Girl, and then comes home to tell AJ all about her. Quinn is increasingly convinced she is “the one.” But he’s reluctant to have AJ meet her, presumably because he finds so much of what AJ has to say about women highly objectionable, and doesn’t want AJ to scare her off.

One of Eddy’s key conceits is that The Girl exists primarily in the minds of these two men. Onstage from the beginning of the play, she flits around, smiling and giggling, and acts out the stories that Quinn tells about their dates. She’s nameless for a reason—she’s a tabula rasa of sorts, a blank slate onto which Quinn projects his romantic hopes. But when AJ forces a meeting between the three, we finally see The Girl as a real person, and learn she may not be exactly who Quinn described.

Johnson does a great job at humanizing a character who might easily come off simply as a mouthpiece for the beliefs of the Men’s Rights Movement. Through Johnson’s performance we occasionally see glimpses of a caring person underneath all the bluster, someone who, in his own perverse way, truly cares about his friend’s emotional well-being, yet is also filled with a simmering rage. Houran is equally good as the likeable, yet socially awkward, Quinn. Houran’s ability to deftly capture Quinn’s profound insecurities is key to helping us understand why Quinn continues to live with such an execrable human being. Eddy’s ear for the puerile humor of straight twenty-something guys feels spot-on, and Johnson and Houran expertly capture the complex nuances of their co-dependent relationship.

As The Girl, Eddy does a lovely job with the difficult task of playing an archetype. But what’s fascinating is that when The Girl finally appears as a real person, rather than the fantasy of Quinn’s description, The Boys Are Angry becomes much more dramatic and visceral. The scene where the Girl first drops by the boys’ house, perhaps the best in the play, deftly makes Eddy’s argument about the necessity of seeing women as real. Unfortunately, in doing so it makes everything that comes before look a bit pale in comparison.

The Boys Are Angry is an intelligent exploration of young white masculinity, all the more arresting having been written by a woman. There are a few missteps: Sam Plattus’s direction drags a bit in the second half, and the final crucial moments (which I won’t spoil here) are curiously hidden behind a couch. And while Eddy’s original song “Don’t Say No” is at turns beautiful, sad, haunting, and creepy, by the end of the play it is also a bit overused; this is a case where I think less would definitely be more. But these are relatively minor quibbles. The Boys Are Angry is intense, powerful theatre that forces us to consider what can happen when men—whether they hate women or love them—refuse to take “no” for an answer.

(The Boys Are Angry plays at VENUE #17: The SoHo Playhouse, 15 Vandam Street, through August 28, 2015. Performances are Fri 8/14 at 5; Tue 8/18 at 7; Fri 8/21 at 2:30; Sun 8/23 at 3; Fri 8/28 at 9:15. There is no late seating at FringeNYC. Tickets are $18 and are available at fringenyc.org.)