The Lehman Trilogy

By Stefano Massini; Adapted by Ben Power; Directed by Sam Mendes

Produced in collaboration with the National Theatre and Neal Street Productions

Off Broadway, Play

Runs through 4.20.19

Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue

by Dan Dinero on 4.2.19

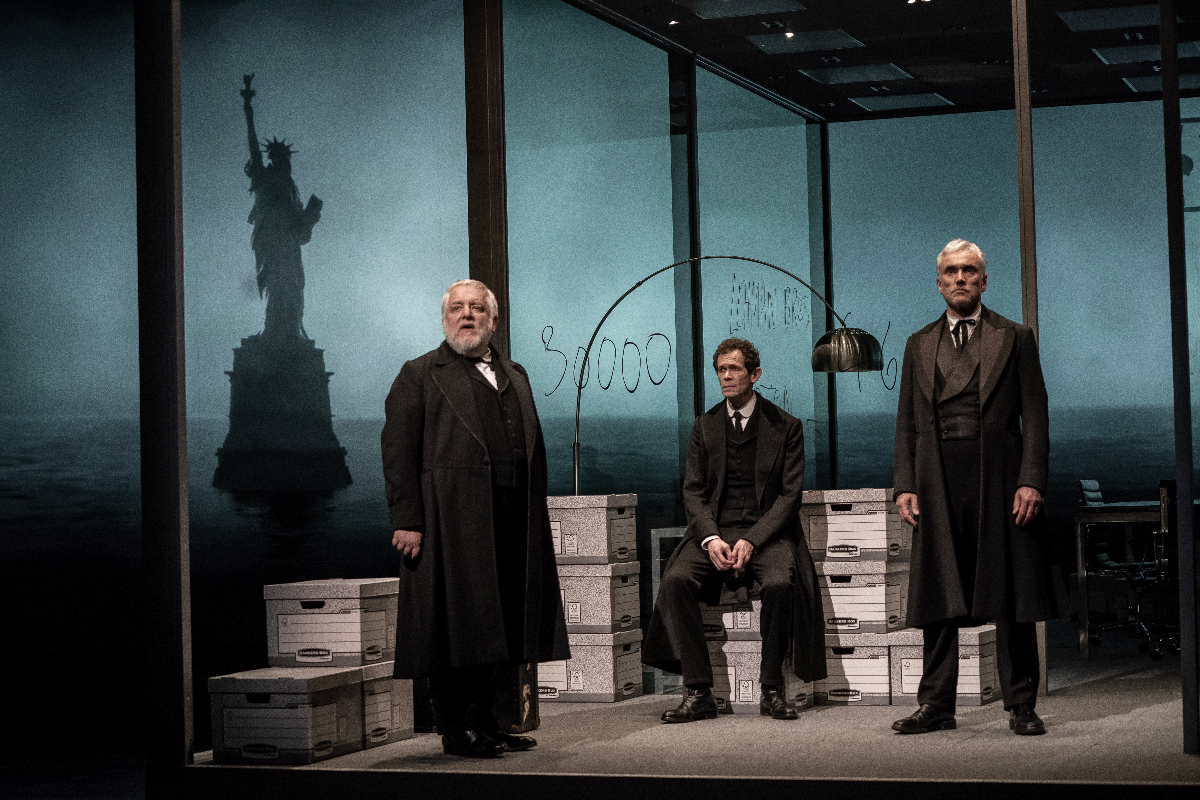

Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, and Ben Miles in The Lehman Trilogy. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, and Ben Miles in The Lehman Trilogy. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

BOTTOM LINE: The story of capitalism in the U.S. told through one family business, The Lehman Trilogy is thrilling theatre—for the head, if not the heart.

Capitalism. If you were to sum up the United States in one word, this is definitely a contender. It’s certainly the argument at the heart of The Lehman Trilogy, an epic sweep of the last two centuries of American history, told through the lens of the most famous of banking families, the Lehman Brothers. It’s a production that humanizes the forces that have shaped our modern life but that also resists (perhaps strategically, perhaps not) letting us empathize too deeply with the men at its center. That it does so is both a strength and a weakness: as accessible as The Lehman Trilogy is (you don’t need any previous knowledge), it’s definitely a piece that engages your mind, as opposed to moving your soul.

In one sense, The Lehman Trilogy is entirely plot—imagine a history book come to life. The text is largely narration, provided by an extraordinary cast of three. We meet Henry Lehman (Simon Russell Beale), the first of his family of Bavarian Jews to come to America in search of a better life. After establishing a fabric store in Montgomery, Alabama, he is soon joined by his brother Emanuel (Ben Miles) and then Mayer (Adam Godley). The first act charts how the brothers move from selling fabric to cotton; after a destructive fire, they get into the business of providing credit to the surrounding plantations. The act ends with Henry dead, and Mayer moving to New York City to join his brother Emanuel, who has used the “opportunity” of the Civil War to turn the company into a bank.

In Act 2 we see how the business gets passed down to, or perhaps taken over by, successive generations of Lehmans. There’s Mayer’s son Herbert (Miles), who advocates for responsible restraint (you can guess how that works out for him). There’s also Emanuel’s son Philip (Beale), who pushes for investments in tobacco, oil, and trains, and is the first to understand that Lehman Brothers is actually in the business of using money to make money. And then there’s Philip’s son Bobbie (Godley), who will take the reins from his father and guide the firm through the tremendous changes of the first half of the 20th century. And then in Act 3, after Philip and Bobbie (whose one son did not join the family business) strategize how best to weather the Stock Market crash, two outsiders—banker Pete Peterson (Beale) and trader Lew Glucksman (Miles)—take control, and dictate the ethos that will lead to company to enormous success before its spectacular collapse.

Although there are many more characters (all played by Beale, Miles, and Godley), Ben Power’s adaptation of Stefano Massini’s script wisely focuses on these few key players, so things never get confusing. The performances are outstanding in their subtlety and restraint; never showy or histrionic, these actors, without the aid of any extra props or costume pieces, create vivid portraits of men most of us have likely never heard of.

Es Devlin’s set is deceptively simple: a group of three rooms (fittingly, sized to the Golden Ratio) is separated by interior glass walls, as if someone took a cross-section of a midtown Manhattan office building. Yet Devlin and director Sam Mendes also seem to have taken inspiration from one character’s comparison of New York to an ever-changing music box: as the set spins round and round, the actors continually remake the interior by moving some very multi-purpose file boxes. The modern black and chrome office furniture is contrasted throughout by the decidedly period costumes by Katrina Lindsay. The men never change out of their 19th-century black suits with long coats, a reminder that the past continues to be alive in the present.

Jon Clark’s lighting design is perfect in its simplicity, using mostly yellows and whites to striking effect on the monochromatic set and costume design. Nick Powell’s music and sound design is similarly unobtrusive, especially in such a cavernous space—the actors are all clear as a bell, without the constant awareness (so present in many Broadway theatres today) that they are speaking through microphones. Along with sound effects that complement without overshadowing, there is also a crucial piano underscore played live. And finally, there are the projections by Luke Halls, which hit the right balance of the literal and figurative. They come most alive in the third act when they spin in an opposite direction to the set, leading to an effect that is as magical as anything you might see at Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

Like many history books, The Lehman Trilogy doesn’t spend much time on the recent past; if you are looking for a deep analysis of why Lehman Brothers failed, you won’t find it here. The play is more concerned with telling the story of capitalism through a single family. And like capitalism, The Lehman Trilogy doesn’t care much about the politics of race or gender, issues that are particularly prevalent in contemporary theatre. While there are a few female characters (also played by the men), they’re mostly of the blink-and-you’ll miss them variety, introduced almost solely for their function as wives and daughters. Given its project, that the piece centers around straight white men is understandable. But while it never celebrates this fact, it also never questions or problematizes it, an approach that some may find frustrating.

And much like capitalism, there is also little attention given to who gets hurt along the way. That the Lehmans built their business on the backs of slave plantations, the Civil War, and the Great Depression, finding opportunity in others’ misfortune, is quite clear, as is the suggested foreshadowing of this to Lehman Brothers’ ultimate fate; much like the set, what goes around comes around. But what’s striking is how much more attention is given to the suicidal stockbrokers than to the starving families produced by Wall Street’s greediness.

In some ways, it’s a shame that The Lehman Trilogy skimps on such topics. But it’s also clarifying: no piece can be about everything, and if nothing else, The Lehman Trilogy knows what it’s about. Rather than race or gender, the piece seizes upon the brothers’ Jewish faith as an over-arching theme. Their religious practice is foregrounded in act 1, but becomes less and less important as time moves on—as the enormous program points out, this epic play is about “a family and a country losing its faith.” But ultimately, The Lehman Trilogy offers no final judgment on what this all means, or where to go from here. Like any good story, that’s up for the audience to decide.

(The Lehman Trilogy plays at the Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue at 67th Street, through April 20, 2019. Running time is 3 hours 30 minutes, with two intermissions. Performances are Mondays through Thursdays at 7; Fridays at 7:30; and Saturdays at 1 and 7:30. Tickets originally started at $35 for previews and $45 for regular performances, but the only remaining tickets in advance are premium seats at $425 per ticket. $45 rush tickets are available day of performance at the box office, starting at noon. There will also be a cancellation line, starting 2 hours before each performance. For tickets and more information call 212-616-3930 or visit armoryonpark.org.)

The Lehman Trilogy is by Stefano Massini and adapted by Ben Power. Directed by Sam Mendes. Set Design by Es Devlin. Costume Design by Katrina Lindsay. Video Design by Luke Halls. Lighting Design by Jon Clark. Music and Sound Design by Nick Powell. Music Direction by Candida Caldicot. Movement by Polly Bennett. Associate Director is Zoé Ford Burnett. Associate Set Designers are Machiko Weston and Matteo Mastrandra. Associate Lighting Designer is Ben Pickersgill. Company Voice Work by Charmian Hoare. Stage Managers are Jane Suffling, Nik Haffenden, Cynthia Cahill. Assistant Stage Manager is Tasha Savidge.

The cast is Adam Godley, Ben Miles, and Simon Russell Beale, with Ravi Aujila. Pianists are Candida Caldicot and Gillian Berkowitz.